Introduction

The choice of isolation valves in the complicated structure of fluid control is hardly a good/bad decision; it is an optimization problem of hydrodynamics, material science, and operational expenditure (OPEX). When engineers are developing pipelines in various industries such as petrochemicals to water treatment, they often have a choice of two rotational heavy weights: the Plug Valve and the Ball Valve.

Although both mechanisms use a quarter turn(90-degree) actuation to break flow, both have a common ancestry of speed and efficiency, but the similarity stops at the surface. They differ in their internal topology, i.e. how they cope with friction, sealing ability and volumetric displacement. The ball valve is the current standard of clean, low-torque efficiency, and the plug valve is the historical titan, often the preferred choice due to its ruggedness and capability to seal where others fail. An incorrect valve type selection in this case is not just an inefficiency, but a possible failure point. This guide breaks down the mechanical difference of these two control valves in order to offer a strict guideline to selection for industrial applications.

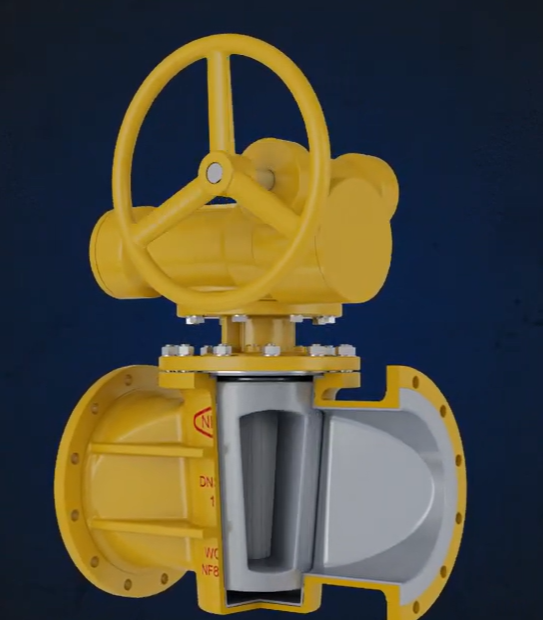

What is a Plug Valve?

One of the oldest and strongest designs of valves in existence is the plug valve. It boasts a simple design, structurally made of a body containing a tapered or cylindrical plug with a bored passage. The basic mechanism is similar to that of a cork in a wine bottle, but made of cast iron, stainless steel, or alloy. The rotating plug spins in the valve body as the stem spins. Due to the conical plug form, the plug fits deeply into the respective seat of the body. This design is based on the high surface area contact between the plug and the surface of the body to form a seal. It is a brute force and simplicity mechanism; the large area of contact guarantees a tight seal but inherently creates a lot of friction in the process.

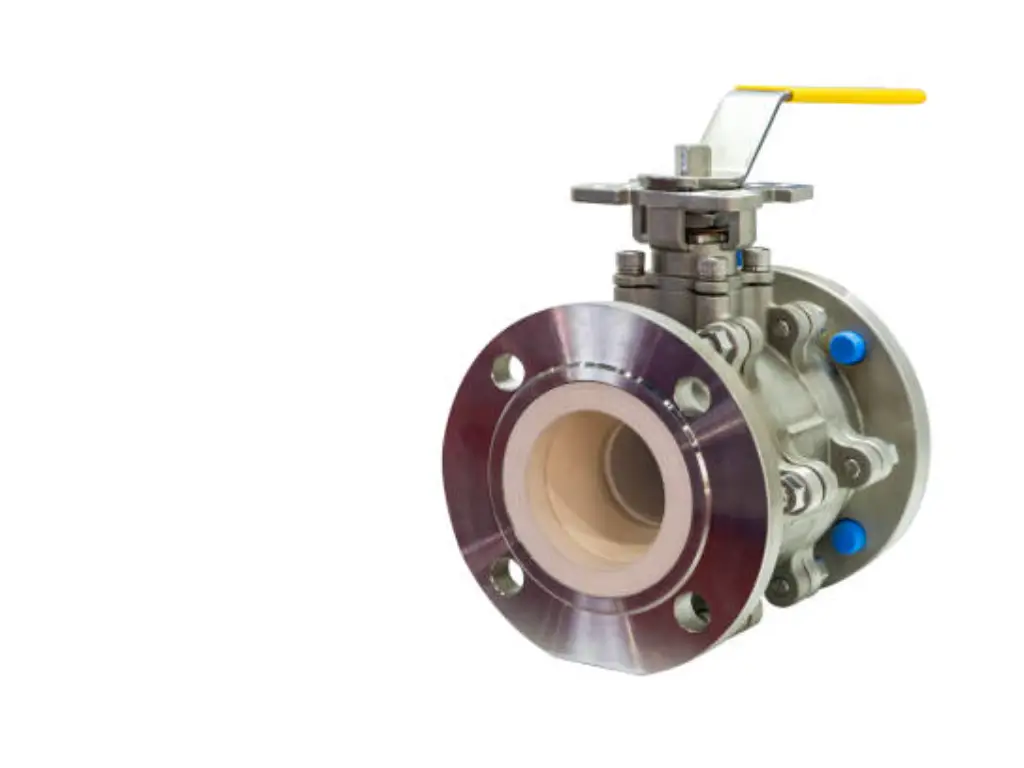

What is a Ball Valve?

The ball valve is a kinematic development aimed at minimizing the friction of the plug designs. Rather than a solid tapered wedge, it uses a spherical disc or closure element, a ball, with a hole cut through the center. The ball is held in the valve body, usually between two soft valve seats of such materials as PTFE or PEEK. The ball valve slides as opposed to the plug valve which grinds surface-against-surface. The contact area is limited to the seat rings which facilitates smoother fluid flow, reduces drag, and can operate with low torque even at high pressures.

Plug Valves vs. Ball Valves: 9 Big Differences

These valves look like they can be interchanged to the untrained eye. But in fluid dynamics and mechanical engineering terms, they operate under other limitations regarding fluid movement. We compare these differences on critical vectors.

Fast Comparison Chart: See the Differences in Seconds

Feature | Plug Valve | Ball Valve | Key Takeaway |

Sealing Principle | Mechanical Interference: Tapered wedge, 360° surface contact. | Pressure-Assisted: Floating ball, narrow line contact against soft seats. | Plug valves offer a robust, permanent seal; Ball valves depend on line pressure. |

Operating Torque | High: Typically 2-3x higher due to constant surface friction. | Low: Low-friction design allows for easier operation and compact actuators. | Ball valves reduce automation hardware costs significantly. |

Dead Space (Cavity) | Zero (Cavity-Free): Solid plug fills the body. No trapped media. | High: Cavity exists between ball and body; traps fluid/bacteria. | Plug valves prevent cross-contamination and bacterial growth. |

Throttling Ability | Good: Inherently linear flow; metal sleeve resists high-velocity erosion. | Poor: “Quick opening” causes wire-drawing; requires specialized V-port. | Plug valves handle flow regulation better without modification. |

Size & Weight | Heavy & Tall: “Solid block” mass makes it 30-50% heavier. Requires high vertical clearance. | Light & Compact: “Hollow sphere” structure is lighter and fits tighter spaces. | Ball valves are the winner for offshore/marine or weight-sensitive projects. |

Scalability | Limited: Friction increases exponentially (“Friction Wall”). Hard to scale >24-36″. | Excellent: Trunnion ball valve design handles load easily. Easily scalable to 60″+. | Ball valves are the standard for large-bore transmission lines. |

Thermal & Pressure Stability | High: Uniform metal expansion; no soft seats to melt or creep. | Restricted: Soft seats (PTFE) deform/extrude under high temperature ratings or stress. | Plug valves are safer for steam and high-temperature/pressure service. |

Maintenance & Lifespan | In-Line Renewal: Seal injections restores seal without shutdown (20-30yr life). | Replace-to-Fix: Requires shutdown to replace worn seats (Variable life). | Plug valves offer superior uptime in critical continuous processes. |

Pigging Capability | Limited/No: Rectangular ports restrict flow and block cleaning pigs. | Excellent (Full Port): Straight-through circular bore allows pig passage. | Ball valves (Full Port) are essential for pipelines requiring regular cleaning. |

Cost Profile (TCO) | High CAPEX / Low OPEX: Expensive to buy, cheaper to run in severe service. | Low CAPEX / High OPEX: Cheap to buy, expensive to maintain in dirty service. | Ball valves = Economy choice. Plug valves = Performance choice. |

How They Work and Seal

Although both are quarter-turn valves that turn 90 degrees to cut off flow, their internal mechanisms and sealing principles differ radically.

A plug valve operates on a mechanical interference fit. It is made of a tapered or cylindrical cone (the plug) which turns within a corresponding sleeve. The seal is not produced by the flow of fluid or pressure but by the physical wedging of the plug into the sleeve. This forms a huge, 360-degree sealing surface that is permanently energized. The main benefit of this is that the seal is strong and does not depend on the line pressure but this constant surface-to-surface compression creates high friction, which requires more torque to run.

By contrast, a typical floating ball valve is based on pressure-assisted sealing. The valve has a floating sphere with a hole between two soft rings of the seat. When the valve is in the closed position, the upstream fluid pressure forces the ball downstream to compress it against the rear seat to create a seal. The action of these is passive; unless there is enough pressure on the line, the seal may be feeble. Moreover, a thin line of contact is used to make the seal. Although this reduces friction and torque, it implies that the integrity of the valve is dependent on a thin and fragile contact line that does not provide much redundancy as compared to the large surface area of a plug valve.

The “Dead Space” Issue (Trapped Media)

A very important, and underestimated distinction is the internal geometry in terms of trapped media. Normal ball valves have a dead cavity, which is the annular space between the open position and closed stroke of the valve. During the open and closed stroke of the valve, a fluid is literally trapped in the bore of the ball and is held in this body cavity. In the case of general water service, this does not matter. But in chemical processing this trapped volume is a great liability. When the liquid is a polymerizing substance (such as monomers or glues), it may solidify in this cavity, effectively trapping the valve and making it unusable. Likewise, in the food and beverage sector, this stagnant zone serves as a breeding ground of bacteria and standard ball valves are not suitable in sanitary lines unless they are disassembled frequently or under special cleaning procedures.

Plug valves, on the other hand, are structurally different because they are cavity-free. The solid plug turns in a sleeve that fits snugly against the valve body and does not leave any volumetric space where media can be trapped. The plug mechanism itself essentially fills the valve body. This geometry of solid block does not involve the possibility of cross-contamination or stagnation of products regardless of the fluid type. Plug valves are therefore technically better in the case of reactive chemicals that may crystallize, slurries that may settle and block a cavity, or corrosive media where trapped fluid may lead to localized corrosion of the valve body internally outwards.

Automation Economics and Operational Torque

The determinant of the economics of valve automation is operational torque, and the structural variations between plug and ball valves introduce a large performance gap. The high torque of plug valves is due to their sealing mechanism: they are based on a high surface area of contact between a tapered or cylindrical plug and the sleeve/liner of the valve body. This surface sealing design produces a lot of friction, especially resulting in a sharp increase in breakaway torque (the force required to move the valve out of a static position). Ball valves, in contrast, have a design that is based on a floating or trunnion-mounted design, in which the polished sphere is in contact with low-friction soft seats (like PTFE), which creates smooth operation with low resistance.

This disparity is clearly quantified by industry data. With the same size and pressure ratings (e.g., ANSI Class 150), the operating torque of a plug valve is usually 2 to 3 times greater than that of a ball valve. As an example, a typical 4-inch ball valve may need about 150 Nm of torque to operate, but a similar plug valve controls may need a driving force of more than 400 Nm.

This difference in torque is what directly determines the choice and the price of automation hardware. Actuator pricing and sizing are directly proportional to the torque output, so to automate a plug valve, heavy-duty pneumatic or electric actuators are needed. This requires increased initial capital expenditure (CAPEX) and leads to heavier and larger assemblies. On the other hand, the low-torque characteristic of ball valves enables the application of small and energy-efficient actuators. In large-scale industrial systems with hundreds of automated valves, the focus on ball valves will result in significant savings in hardware costs and long-term energy use (OPEX).

Flow Control Capabilities

Although both types of valves are designed to operate as on-off isolators, their behavior is quite different when they are forced to operate as throttling devices. To a great extent, this difference is based on the variations in their port geometry and seat support systems.

The flow characteristic of standard ball valves is usually that of a quick-opening type, which is not well suited to regulation or precise control. A typical round-port ball valve is broken open and the high-volume surge of fluid is released instantly. This forms a high velocity jet stream that is concentrated at the slimmest section of the soft seat. This causes a phenomenon in throttling services called wire drawing, in which the fast-flowing fluid cuts channels into the exposed PTFE seat, quickly eliminating the capacity of the valve to close tightly. Ball valves have poor control and wear out easily unless a special, non-standard, V-port ball is used, and this is not a standard feature.

On the contrary, plug valves are naturally more robust in throttling tasks, managing flow rate effectively. The major distinction is in the geometry of the port; the plug is usually a rectangle with an opening. The variation in the area of flow is more directly proportional to the motion of the handle than to a round ball port, and the flow curve is more linear and predictable.

More importantly, the design of the plug valve is more resistant to the erosion due to throttling and minimizes pressure drop issues associated with wear. The sealing sleeve of a plug valve, unlike the floating or protruding seats of a ball valve, is completely recessed and firmly fixed to the metal body, and it is a large area of coverage. This strong design eliminates the deformation and washout of the seat that is common with high velocity fluids. Although they lack the fine control of a dedicated globe control valve, plug valves are much more robust in use where coarse flow control is needed or where they need to be left partially open.

Size and Weight

The internal geometry of these valves determines their physical footprint, namely the difference between the solid block and hollow sphere. This difference is more critical with the increase in the diameter of the pipes.

In small pipe diameters (less than 4 inches) the difference in weight is insignificant. But in larger industrial use, the weight of the solid metal plug presents a large weight penalty. An example is that in a 12 inch ANSI 150 assembly a plug valve may have a weight of about 380 kg, but a similar floating ball valve has a weight of about 250 kg, a difference of more than 30 percent. Although the face-to-face dimension of plug valves is usually smaller (conserving space in the pipe axis), the overhead adjustment mechanisms and heavy-duty actuators need a lot of vertical clearance. Therefore, in offshore platforms or marine vessels where structural weight is a premium consideration, the ball valve is nearly universally used.

Scalability and Customization

The relationship between surface area and friction determines the possibility of scaling these valves to large diameters.

Ball valves are very scalable and are used in the industry where large-diameter pipelines (up to 60 inches or more) are used. This is enabled by the trunnion-mounted design in larger sizes which holds the ball at the top and bottom. This mechanical support takes the load of the line pressure and the ball does not grind on the seats and the operating torque is manageable. As a result, it is a simple engineering task to produce a huge ball valve, and they are not very heavy or expensive even in large sizes.

Plug valves, however, have a friction wall as they increase in size. Since the design depends on the contact of the total area of the plug surface to seal, the valve size doubles exponentially, and thus the contact area, and therefore the friction. Very large plug valves need huge torques to open, and large, costly, and slow-responding actuators are required. Also, the solid metal plug is extremely heavy, which poses structural support problems. It is due to these reasons that plug valves are seldom encountered in sizes larger than 24 to 36 inches in standard practice, since the ball valve is by far the better choice in large bore transmission lines, in weight, cost, and operation.

Pressure Resilience and Thermal Stability

The root cause of the performance difference in extreme conditions is the soft seat limitation vs. structural geometry. Normal ball valves use thermoplastic seats (such as PTFE) that is the unique weak point in high-stress applications. These polymers experience thermal creep under high temperatures, that is, they become soft and permanently deform under compressive force of the ball. When high pressure is applied concurrently, the softened seat may physically extrude into the bore and destroy the seal. Moreover, the difference in thermal expansion between the polymer seat and the metal ball is unstable: the seat expands at a slower rate than the steel, and the valve is seized when hot or the system experiences blow-by leakage when it cools down.

Plug Valves (especially lubricated or metal-seated ones) are in contrast based on a tapered interference fit spread over a huge surface area instead of a thin, delicate ring. This geometry is dimensionally stable in nature. Since the plug and the body are usually of the same metallurgy, they contract and expand together under heat, preserving the seal geometry without the danger of melting or deformation. A ball valve puts pressure loads on a narrow line of contact (prone to crush the seat), whereas the plug valve spreads pressure over the entire broad face of the plug, enabling it to survive in steam or high-pressure service where soft-seated valves would inevitably fail.

Maintenance and Lifespan

The maintenance policies of these valves are two conflicting philosophies: in-line renewal and component replacement.

Lubricated plug valves are made to work continuously without dismantling. When the valve finally starts to leak through wear, the operator can inject a special sealant into the line through an external fitting when the line is still pressurized. This sealant is carried to the seating surface via internal channels, and essentially, it is a renewable liquid gasket that fills scratches and restores integrity immediately. This feature enables plug valves to last decades even in severe conditions.

Ball valves on the other hand are usually run to failure. Their durability is solely dependent on the state of the soft seats (such as PTFE or PEEK). When this soft material is washed away by the flow or scratched by debris, the seal is permanently damaged. It cannot be repaired externally, the line has to be closed and the valve taken off or dismantled to fit a repair kit. Although ball valves can have a service life of more than 10 years in clean gas service, their life can be reduced to a few months in abrasive slurry service, and thus is a consumable product in dirty service.

In-depth Cost Analysis

In order to fairly compare the cost of Ball Valves and Plug Valves we need to consider more than the sticker price and examine the financial implications of the entire lifecycle of the valve. The situation changes dramatically when you consider that you are either interested in short-term savings or long-term sustainability.

Upfront Purchase Price (CapEx): The Ball Valve is the obvious winner in terms of pure initial cost, usually being 25 to 35 percent cheaper than a similar Plug Valve. This is not an arbitrary price difference; the tapered body of a Plug Valve is physically larger, and uses 15 to 20 percent more raw metal, and needs to be ground to a fine finish by hand to provide a seal. Conversely, a Ball Valve is compact and spherical in shape, which enables mass production that is fast and economical.

Automation and Integration Costs: In case your system needs automation, the torque penalty of a Plug Valve adds to its cost. Because of the close friction fit needed to seal, Plug Valves frequently require 2x to 3x the operating torque of floating Ball Valves. This physical reality compels you to buy much bigger and more costly actuators. Therefore, in the case of automated packages, selecting a Plug Valve may increase the overall system price by half or more than the low-friction and energy-efficient Ball Valve solution.

Operational Expenditure (OpEx): The Ball Valve has the advantage in the short term price, but the Plug Valve in the long term reliability in critical lines. The unspoken price of a Ball Valve is its replace-only maintenance model; a seat failure can frequently necessitate a full, costly production shutdown to change the unit. On the other hand, the Lubricated Plug Valve is in-line maintenance. In case of leakage, operators can inject sealant to achieve integrity without halting the process. In this regard, the increased initial price of the Plug Valve is an insurance premium that will be recouped by avoiding disastrous downtime expenses.

Plug Valve vs Ball Valve: Five-Step Self-Audit in the Selection of Industrial Valves

An effective valve selection process is not just a matter of product specifications; it involves a methodical diagnosis of operational priorities, safety requirements, and long-term cost strategy. This five-step self-audit will make sure that your decision is exactly what you want to achieve in your business.

Step 1: The Media Test – What are You Moving?

The first thing is to carefully diagnose the physical properties of the fluid being transferred, which eliminates the wrong type of valves at a glance. In addition to merely deciding whether the media is clean or dirty (has slurries or high solids), the stability of the media over time is also a critical consideration; in fluids that tend to stagnate, polymerize, or decay (organic waste, sewage, fermentable food products, etc.), internal valve cavities are a significant source of contamination or seizure, so cavity-free designs are a non-negotiable requirement. At the same time, when the fluid is hazardous or toxic, the integrity of the sealing element will become the most important factor to avoid fugitive emissions whereas operational considerations such as pigging of the pipeline will further reduce your choices to Full Port designs.

Step 2: The Control Audit – How Often do You Operate?

Then assess the working pace and management techniques. Identify whether the valve is used rarely (e.g., a few times a year) or often (e.g., every hour/day). The low-frequency components are required to reduce wear because of high-frequency operation. When remote control or automation is necessary, then an actuator is introduced, so actuator torque is an important consideration to size. In case the process needs to be controlled with a fine flow modulation (throttling), then regular on/off valves should be excluded in favor of special designs, including V-Port regulating valves.

Step 3: The Environment Check – What are Your Constraints?

Physical constraints are presented by the installation environment and have a drastic effect on the choice of valves. First, determine the space and weight limitations of the piping design, as heavier or larger designs might need extra structural support. Then, there is the temperature and pressure of the system, which predetermines the required pressure Class rating and defines whether standard soft materials will be able to withstand the environment. Above all, consider the physical accessibility of the place of installation: in case the space is narrow, inaccessible, or the valve must be permanently welded into the line to prevent any accidents, it is impossible to take the unit out of the line to service it. Thus, you need to decide whether or not your application needs to be inline repairable (capable of servicing internal parts without disassembling the body). Finally, make sure that the piping is compatible, and that the connection standards of the valve are compatible with your existing system.

Step 4: The Cost/Strategy – What is Your Budget Philosophy?

The choice of valves should be in line with the long-term financial plan in terms of Total Cost of Ownership (TCO).

Determine your priority: do you want the first purchase cost (CapEx), where small actuators on automated ball valves can save you, or the long-term cost of operation (OpEx), where maintenance (such as frequent lubrication) is the order of the day?

Maintenance strategy: Prefer preventive maintenance, scheduled maintenance, or running the valve until it breaks (reactive)? The strategy selected determines the budget that will be allocated to the maintenance staff and spares.

Step 5: The Maintenance and Service Test – How will You Service this Valve?

The last step deals with the reality of long-term living with the valve, which is about your facility Maintenance Culture and Supply Chain strategy.

Determine your operational preference: do you have the manpower to do Preventive Maintenance, i.e. the rigid lubrication schedule Plug Valves needs to avoid seizing? Or would you rather have the install-and-forget quality of floating Ball Valves, which normally operate until they break down (Corrective Maintenance)?

Consider Spare Parts Complexity: standard ball-valve soft seats are usually off-the-shelf commodities that minimize Mean Time To Repair (MTTR), but proprietary sealants or custom-ground plugs may cause supply bottlenecks.

Evaluate Technician Training: select a valve technology that compliments the current level of skills of your maintenance team to prevent operational mistakes during servicing.

Which Valve should You Choose?

It is not a question of which is better or worse, but which one will last in your particular working environment. Following the steps of the audit above, the following is how to match your particular needs to the appropriate type of valve.

Best Uses for Plug Valves

This valve should be specified where the integrity of the seal, extreme media resistance, and long-term reliability are more important than a small footprint.

-

When you are dealing with dirty or abrasive media: When your pipeline is carrying slurries, sludges, or fluids with solid particles, the soft seat of a standard ball valve will soon be eroded. In this case, you are to choose a Lubricated or Non-Lubricated Plug Valve. Its quarter-turn motion forms a wiping effect that keeps the seating surface clean each time you use it, so that the debris does not embed itself in the seal.

-

When your media is likely to Spoil or Stagnate (Critical to Hygiene/Safety): When you are transporting organic waste, food pastes, or glues that can rot, ferment, or solidify when trapped, do not use a standard ball valve. The ball valves possess a dead space behind the ball where fluid gathers and decays. Rather, select a Sleeved Plug Valve. It is cavity-free in nature, and the sleeve entirely encloses the plug, leaving no holes where bacteria or solids can conceal themselves, keeping the line clean and free of seizures.

-

When you need Zero-Leakage in Hazardous Service: When dealing with lethal gases or high-value chemicals, and a leak is not an option, the Lubricated Plug Valve is your best choice. It also has the advantage of being able to inject sealant directly into the seat when the valve is under pressure, which forms an instant, renewable seal barrier that ensures complete isolation.

-

When the valve will be idle months (Infrequent Operation): Valves that are not operated frequently are likely to freeze or stick. In case you are using annual isolation in your application, select a Plug Valve. Its powerful, high-torque design enables you to exert the required force to overcome any obstacle and close the line with certainty even after years of inactivity.

-

When Maintenance means expensive downtime: When the valve is welded into the line or in a difficult-to-reach location, you must have a valve that can be maintained in place. Lubricated Plug Valves enable your technicians to regain sealing performance by merely injecting sealant, and not incurring the huge expense of cutting a valve out of the line.

Best Uses for Ball Valves

It is the best option in clean media, high frequency operation and where the main constraint is the budget and space.

When you require High-Cycle Automation (Optimizing OpEx): When you have production lines that open and close hundreds of times per day, the Soft-Seated Ball Valve cannot be beaten. It is designed with a low-friction design, which allows the use of smaller, cheaper actuators. This saves you a lot of money in initial set up and saves on energy in the long run.

Space and Weight Constrained: Do you need an offshore platform, skid-mounted system, or a tight pipe rack? Choose the Ball Valve. It has a far greater flow capacity-to-weight ratio than the heavy, tapered body of a plug valve. A ball valve will accomplish the same task with a smaller footprint and with less heavy structural support.

When the Media is Clean (Water/Air/Gas): In general utility lines where the fluid is non-abrasive, a Plug Valve is generally unnecessary. You are to select a Standard Ball Valve, which offers Class VI (bubble-tight) sealing at a fraction of the price. A Plug Valve would be a strategically inefficient choice in this case: its high-friction design will naturally produce significantly more torque, and you will have to buy oversized and costly actuators just to rotate it. Moreover, you would be taking on an unwarranted maintenance cost (e.g. periodical lubrication) on a simple application where a maintenance free ball valve would serve well over years. Basically, do not pay a high price on heavy-duty abrasion resistance that will never be used by clean water or air.

When you have to Pig the Pipeline: When you have to send cleaning pigs down the line, you are virtually limited to a Full-Port Ball Valve. It is made to fit perfectly inside the internal diameter of the pipeline, and the pig is free to go through without any obstruction, which most plug valves cannot.

If you require Flow Throttling (Control): Standard valves will not work if you require to control flow and not merely to stop it. Nevertheless, a V-Port or Segmented Ball Valve is a good solution. The V-shaped notch alters the flow path to give a fine, linear control, enabling you to use a ball valve to regulate the flow without ruining the seat.

The Strategic Upgrade: Manual Limitations to Automated Control

In the case of such industries as fine chemicals or natural gas, the use of manual valves introduces unseen bottlenecks. The inconvenience of intermittent batch quality or the fear of working in dangerous areas with valves are not mere inconveniences, but are operational risks.

Assess whether your operations are bedeviled by the following basic problems before automating:

The Accessibility Trap: Valves in dead zones (high heat, pits, or heights) are hard to access, and as a result, equipment is frequently neglected.

Personnel Risk: Technicians should not be sent to work in hazardous places to turn handwheels because it imposes unwarranted safety risks on the staff.

Reaction Lag: A human operator can simply not physically close a large valve in milliseconds in an emergency involving pressure spikes.

The Precision Barrier: Manual throttling is nothing but a guess. The 0.1% consistency of quality cannot be done by any human hand.

Automation addresses these pain points by replacing the concept of Field Operation with the concept of Centralized Control, turning individual mechanical components into a responsive, unified system. In order to justify the investment, the following table measures the operational difference between manual reality and automated advantage:

Feature | Manual Valve Reality | Automated Valve Advantage |

Precision | ±10% Error. Relies on rough estimation. | 0.1% Accuracy. Digital positioners ensure exact dosing. |

Response | > 15 Mins. Detection + travel + cranking time. | < 2 Seconds. Instant sensor-triggered isolation. |

Safety | High Risk. Requires physical entry to hazard zones. | Zero Risk. 100% remote operation from control room. |

Labor | 1:1 Ratio. One technician per valve. | 1:500 Ratio. One operator manages the whole plant. |

Torque | Limited. Dependent on human strength. | Unlimited. Heavy-duty actuators overcome friction instantly. |

The choice to automate is not the last one. In order to achieve success, you should set four technical parameters:

Actuation Source: Pneumatic, because it is fast and safe; Electric, because it is accurate.

Control Logic: On/Off to isolate; Modulating (with smart positioners) to control flow.

Fail-Safe Mode: Determining whether the valve should Fail Open, Fail Closed, or Lock in Place when power is lost (important to safety).

Torque Sizing: It is always better to use a Safety Factor of 25-30 percent to make sure that the valve cycles reliably even when it has not been used in a long time.

To convert these complicated specifications into assured field performance, you require a partner who can do accurate engineering and flawless integration, this is where Vincer comes in.

Why Vincer is Your Reliable Automated Valve Partner?

The choice of an automated valve solution is an engineering task that cannot be achieved by a product catalogue only; it needs accurate system integration and uncompromising confidence. Vincer offers this guarantee by integrating profound engineering expertise with a decisive cost effectiveness edge, namely, in complex control systems.

Failure to automate is usually caused by improper sizing or mismatched specifications and this is the reason why Vincer eradicates this risk with our core Engineering Authority. We have a dedicated group of 10+ senior engineers with an average of more than 10 years of experience, which is more than just a normal selection. We carefully examine your automation requirements on eight key dimensions that are critical- a process that is much more detailed than the industry standard. This guarantees that all actuators are optimally calibrated to your media, pressure and temperature conditions.

We back this engineering accuracy with a strong, self-managed portfolio of approximately 20 automated valve sub-categories. You need pneumatic systems in hazardous conditions or electric valves in fine-tuning, our solutions are supported by international standards such as ISO9001, CE, RoHS, SIL, and FDA. This will ensure that your automated system is of the best international safety and hygiene standards.

Vincer provides straightforward quotes within 24 hours in fast-tracked industrial projects where time and budget are paramount so that your procurement process will never come to a halt. Above all, we maximize the ROI of your project. Our general-purpose automated valves are of high quality and cost 30 percent less than the best European brands, and our specialty electric and solenoid valves can save 50 percent of the cost of the same performance level. Select Vincer to achieve the best automated control at a lower cost.

Certain Classifications of Plug Valves and Ball Valves

Choosing an appropriate manufacturing partner is one thing, but the other is defining a specific hardware setup. Although the broad categories are Plug Valve and Ball Valve, the performance of these types in the field is determined by certain internal design variations.

To assist you in narrowing down a broad idea to an exact specification, the next section subdivides the detailed classifications of these two families of valves in terms of their sealing mechanisms and functional designs.

Types of Plug Valve

The classification of plug valves is primarily based on the approach to controlling friction and ensuring the large sealing contact area.

Type | Classification Basis | Key Mechanism | Primary Use |

Lubricated Plug Valve | Sealing/Friction Management | Injects sealant (grease) to lubricate and form the primary seal. | High-pressure gas, dirty hydrocarbons, critical service requiring in-line seal renewal. |

Non-Lubricated Plug Valve | Media Isolation | Uses a resilient polymer sleeve (PTFE) for sealing and isolation. | Chemical, food processing, and purified water where media purity is essential. |

Eccentric Plug Valve | Operation Kinematics | Plug lifts away from the seat before rotating. | Wastewater, sludge, and heavy slurries; prevents seizure and reduces wear. |

Multi-Port Plug Valve | Flow Passage Quantity | Plug features multiple bored passages. | Flow diversion, switching, or blending in complex pipelines. |

Types of Ball Valve

The classification of ball valves is mainly determined by the mechanism that supports the ball (determining the pressure rating) and the geometry of the flow passage (determining the flow characteristics).

Type | Classification Basis | Key Mechanism | Primary Use |

Floating Ball Valve | Ball Support Mechanism | Ball is unsupported; upstream pressure pushes it against the downstream seat. | General utility, low-to-medium pressure service, cost-effective isolation. |

Trunnion Mounted Ball Valve | Ball Support Mechanism | Ball is fixed by anchors (trunnions); seats are spring-loaded. | High-pressure and large diameter lines (above 8 inches); maintains low operational torque. |

Full Port Ball Valve | Flow Passage Geometry | Bore diameter equals pipe internal diameter. | Pipeline pigging and critical lines requiring minimal pressure loss. |

V-Port Ball Valve | Flow Passage Geometry | Port features a V-shaped notch. | Throttling and precise flow control; provides linear flow characteristic. |

Multi-Port Ball Valve | Flow Passage Quantity | Utilizes L-Port or T-Port drilling. | Flow diversion, switching, or blending; single-valve solution for complex fluid transfer. |

Conclusion

The decision between a plug valve and a ball valve is not dichotomous; it is situational. The ball valve is more efficient, less torque, and can be easily automated with clean and high-volume flows. The plug valve has unparalleled durability, sealing integrity, and clogging resistance in dirty, abrasive, or corrosive conditions.

The engineers need to balance the initial capital expenditure and the reality of the long-term operation. A less expensive ball valve that fails during slurry service is a costly error. An unnecessary inefficiency is a heavy plug valve in a clean water line. Knowing the mechanical difference between the two, you are guaranteed of your system running at its theoretical best.

FAQS

Q: Can throttling flow be done with a ball valve?

A: Throttling should not be done with standard ball valves because the seats may be eroded by high velocity. Nevertheless, Vincer provides specialized V-Port ball valves that are specifically aimed at the accurate flow modulation.

Q: Which is the tighter sealing valve?

A: Bubble-tight shutoff can be attained in both. Nevertheless, plug valves tend to preserve this seal longer in abrasive environments because of the high sealing surface area.

Q: Are plug valves more costly than ball valves?

A: Generally, yes. Plug valves are more metal-filled and are cast in a complicated way. The cost difference however becomes smaller in smaller sizes or high-pressure classes and the longevity of the plug valve can provide better ROI.

Q: Does Vincer have the capability to automate both types of valves?

A: Yes. Our entire line of ball and plug valves is manufactured and integrated with both electric and pneumatic actuators, which is a “plug-and-play” solution to your control system.